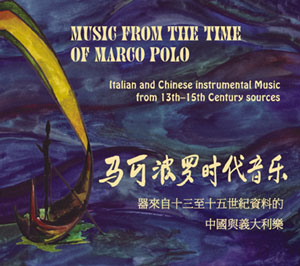

CD "Music from the Time of Marco Polo"

The Centre for Early and Oriental Music FA Schola presents:

CD "Music from the Time of Marco Polo"

1. Istampitta In Pro (7'46'')

2. Chu Ge - Song of Chu (6'50'')

3. Xiao Xiang Shuiyun - Clouds over the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (6'36'')

4. Lamento di Tristano. La Rotta (6'27'')

5. Feiming Yin - Calling out in Flight (5'52'')

6. Eh, vatene, segnor mio (1'27'')

7. La nobil scala (3'08'')

8. E con chaval (2'15'')

9. Nel prato pien di fiori (2'20'')

10. Qiao Ge - Woodcutter's Song (8'07'')

11. Istampitta Belicha and Huo Lin - Captured Unicorn (15'51'')

12. La Manfredina (9'54'')

FA Schola ensemble

Raho Langsepp - medieval flutes

Lilian Langsepp - gothic harp

Helena Uleksin - bell chime, medieval flute

John Thompson - guqin

According to his Travels, Marco Polo (1254-1324) visited Hangzhou some time after 1276, when Mongol soldiers had captured it on behalf of Kublai Khan. Music from the Time of Marco Polo puts music then being played in Hangzhou side by side with music such as Polo could have heard back home in early 14th century Italy. John Thompson plays the former on the Chinese guqin silk string zither, mostly from tablature published in 1425 CE, but clearly copied from earlier sources. The Estonian early music group FA Schola plays the Italian music on flutes, bells and harp; the primary sources are also mainly early 15th century documents (such as London BL. add. 29987; London, British Library, Additional 29987), but also clearly containing older music. Although there is no evidence of actual musical contact at that time, this program expands on the original sources to include the fantasy of such musical exchange. Thus, FA Schola joins with the guqin for Calling out in Flight, while for La Manfredina the guqin joins FA Schola and the Western flute is replaced by a Chinese xun. How this might have happened seven centuries ago is left to the listeners' imaginations.

This program is unique in that, through historically informed performance, it provides a beautiful audio tour of two vastly different cultural areas 700 years and more in the past. What we will find from listening to these two very distinctive music genres is that their two respective musical languages show some very interesting similarities, more than what we might initially expect, and more than what we seem to find in the modern world. And yet the music sounds surprisingly new.

At the time Marco Polo described his travels to China, Europeans were just beginning to write down their instrumental music, but musical styles soon rapidly developed and expanded. Meanwhile, the Chinese guqin silk-string zither tradition was both more developed and more conservative. The guqin, although the only non-Western instrument with a detailed written tradition going back more than a few centuries, had long had such a tradition going back much earlier than what can be documented for Western music: a surviving guqin score from the 7th century already shows a high level of musical sophistication.

The key words uniting these two ancient musical worlds are modality and monodic playing style. Modal thinking (allowing melodies beyond the standard major and minor scales) forms a type of musical knowledge almost gone in present day classical Western music but still found in many oral and popular traditions. And the ensemble playing style in the early West, as in China, is a type of monody in which all instruments play versions of the same melody. Much has been done to reconstruct the monodic ensemble music tradition from medieval Europe. This tradition was also then prevalent in China, and the present reconstructions of the early solo guqin repertoire are a substantial step in efforts at a similar reconstruction of the early Chinese ensemble tradition.